Text: Cardinal Turkson on Archbishop Romero

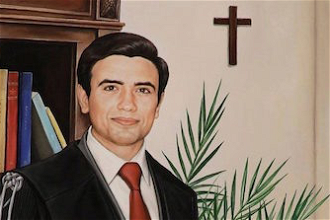

Cardinal Peter Turkson

Ghanaian Cardinal Peter Turkson, President of the Justice and Peace Council in Rome, gave a substantive lecture on 'Archbishop Romero as Preacher and Teacher' at Notre Dame University, Indiana, on 25 March 2011.

Introduction

I bring you greetings from the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. Thank you to President Fr John Jenkins CSC and to Fr Robert S Pelton CSC for the invitation to deliver the annual Oscar Romero Lecture at the University of Notre Dame, in the context of this year's conference on Catholic Social Tradition. You invited me to speak about someone whom I have long admired from a distance of both time and space. In March 1980, finishing a licentiate in Sacred Scripture at the Biblicum in Rome, I was on my way back to Ghana to rejoin the staff at St Theresa's Minor Seminary. Now, providentially, there have been some opportunities recently to draw nearer to Oscar Arnulfo Romero, and this evening it is my honour to share with you a growing appreciation for him. For I feel as though he and I have a lot in common.

Last November my very first trip to Latin America took me to El Salvador to address CELAM's fifth Continental Meeting on Human Rights. After many hours of flying and the long ride from the airport up to the city, I found myself at the Ayagualo Centre, contemplating the surrounding volcanic mountains covered in lush green, the abundant tropical flowers and trees, the song of the birds, humming of insects, forest creatures calling out to each other: yes, I felt como de mi casa, just like

at home. Let me tell you what I discovered there.

1. The Good Shepherd

This evening, I would like to propose that we consider the homily preached by Archbishop Romero on Good Shepherd Sunday, 16 April 1978, in the Church of El Rosario. As you probably know, in the New Testament, when Jesus speaks about the Good Shepherd, he is actually speaking about himself. So when Abp Romero takes up this self-portrait of Jesus, he is unconsciously sketching his own self-portrait, too. Thus the homily provides us with an opportunity to get to know him from within his ministry. "Every homage paid to me," he says, "is really a homage to Christ the Good Shepherd and to your own faith."

Moreover, there are two complementary images of how, in the days of Jesus, a shepherd would lead his flock. In some circumstances, he would go before the sheep and they would follow; here the emphasis is on finding the way, or even making a new way. In other situations, the shepherd would walk behind the flock, from where he could see which sheep or lamb was weak or ill, likely to go astray or already wandered off. For Archbishop Romero, the strays included the rich, the powerful, the violent - those who disagreed with him, those who attacked him.

"Bishops do not rule as despots. At least they should not act in this way. The bishop should be the most humble servant of the community because Jesus told his disciples, the first bishops: let the greatest among you be as the youngest, and the leader as the servant. The command that we follow is one of service. Our way of life and our world is also one of service." So whether leading from before or from behind, a Bishop "now prolongs the person of the Good Shepherd" in the words of Pope Paul VI.

In contrast with the thieves and robbers who, in Jesus' words, "climb in by another way," Archbishop Romero spoke in this way about himself and his fellow bishops: "Those of us who have the honour of being pastors, would not be pastors if we had not been called to enter through the door. The true bishop and pastor, the authentic and only Pope, are those who have entered through the gate - the gate that is Christ."

When Father Romero was ordained a bishop - and the same thing happened to me - these are the prophetic words pronounced by the presiding celebrant: "As a steward of the mysteries of Christ in the Church entrusted to you, be a faithful overseer and guardian. Since you are chosen by the Father to rule over his family, always be mindful of the Good Shepherd, who knows his sheep and is known by them and who did not hesitate to lay down his life for them." And so it was.

2. The Cathedral

During my visit to San Salvador, Auxiliary Bishop Gregorio Rosa Chávez guided us through the noisy, choking downtown traffic to the monumental Cathedral. In the sunlight, the exterior is brightly painted and decorated in a joyous naturalistic style, while inside, one is surrounded with great scenes from the life of Jesus, the Divine Saviour of the World. I know that, nowadays, the cathedral offers quite a different impression than it did during Archbishop Romero's day, when it was just a huge cavern of rough poured concrete, all grey and dark and echoing.

Entering the cool and tranquil oasis, one encounters an ample sacred space for recollection. This is where Archbishop Romero presided and preached every Sunday. With great interest and even astonishment, I listened to Bishop Rosa Chávez describe the complex, conflictual situation of the country in those days, and the enormous difficulties confronting the pastor or shepherd that Archbishop Romero was ordained to be.

During each homily, Archbishop Romero would "dedicate as much time as was needed to narrate the most important events that had taken place that week. In that 'spoken Sunday newspaper', he reported what the national media - controlled and censored by an authoritarian and repressive State - could not report. And his message was broadcast through the Church's own means of mass communication, the Catholic weekly Orientación and, especially, the radio station YSAX, both of which were dynamited on many occasions by death squads and paramilitary groups."

So every Sunday morning people crowded into the Cathedral or were glued to their radios. In towns and villages everywhere throughout El Salvador (since the country is so small), during the eight o'clock Mass at the Cathedral, you could walk the streets and notice that, in each house, store, police station and guard post, Archbishop Romero's Mass was on the radio. An important dialogue was established, as the huge congregation in the cavernous cathedral responded with applause whenever there was general agreement or support for what the preacher said.

On Good Shepherd Sunday in April 1978, Mons. Romero explained: "We are unable to celebrate today in the Cathedral because it is occupied. At the same time four embassies have also been occupied: those of Costa Rica, Panama, Switzerland and Venezuela. The Popular Revolutionary Bloc, who has taken responsibility for this action, wants to put pressure on people so that they do not remain indifferent to the situation that is occurring in the rural areas of our nation. They have occupied the embassies because they want these countries to help them so that they can return to their land. The rains have begun to fall and their fields must be planted. They tell us: If there is no corn in our fields and if we are unable to harvest our beans, then we will die of hunger. The campesinos are right. They want to return to their fields and work and they are asking for the support of those who are able to speak on their behalf: the Cathedral, the embassies and their government. They ask these persons who are able to speak to put pressure on the government of El Salvador so that they can return to their fields and live in peace. They do not want more promises. They want security and guarantees because, they tell us, there have been cases where the campesinos have returned with confidence to their lands only to find themselves being led off to prison once again. We pray that the Lord will resolve this situation!" While Romero "tirelessly defended the right of the poor to organize, he was very critical of popular organizations which became overly or one-sidedly political.…"

In the past, my home country of Ghana was also beset by various types of conflict: chieftaincy, tribal, religious, political, customary feasts, civil society versus state institutions, and electoral politics. So in August 2006, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) helped the Government to set up its National Peace Council (NPC) to address these flash-points and de-fuse tensions, and I became its chairman. The NPC strove to be independent, non-partisan and impartial; it worked to avoid or prevent conflicts from erupting, to consolidate and maintain peace throughout the country. As the chairman of the NPC as well as leader of the Religious Bodies, I authored quite a few peace messages.

Within two years we faced our biggest challenge: the elections of December 2008. Since none of the eight candidates for the Presidency received a majority of votes in the first round of 7 December, a run-off took place on 28 December between the two leading candidates. Akufo-Addo (NPP) got 49.13 % of the votes and John Atta Mills (NDC) got 47.92 %. But when five days later the last constituency reported, the final outcome saw John Atta Mills declared President-elect with 50.23 % of the votes. You can imagine the anticipation before the run-off hand and then, in the wake of a reversal nearly too close to call, the maximum tension and the inherent danger we were in. All the institutional safeguards suddenly seemed absent. There was mutual suspicion and mistrust. The two parties could not talk to each other, and resorted to accusations based on fear and

speculation.

After the run-off of 28 December, I was awakened every morning by a phone call from one or the other Radio Station, asking for a message to calm the population or to advise the politicians. The respect of the Ghanaian public for the Cardinal and the confidence they had in the NPC encouraged us to wade into tempestuous and riotous situations to exhort people to calm, encourage the Electoral Commissioner to be strong and unyielding to pressures and, when all forms of communication appeared to have collapsed, to mediate between the two sides. I am glad that, with the support of other religious leaders, the NPC was able to provide a line of

communication. Thanks be to God, Ghana soon overcame the sort of crisis which has damaged several other African countries, and on 7 January 2009 we were so glad to have our constitutionally-elected President sworn into office.

While I have illustrated the experiences of two different Archbishops in two quite different places and at two very different times, both were engaged in the civic process of their country and played a leadership that was properly religious as well as public, for the sake of the common good, justice and peace. What seems most striking is how differently Archbishop Romero's story turned out, despite our identical shared vocation to serve as a Shepherd in the Church.

A week before his murder, Abp Romero described the conflict surrounding his pastoral ministry: "Those who think that my preaching is political and incites people to violence and who believe that I am the cause of all the evils in our country have forgotten that the Church's word does not invent the evils of the world. Rather it casts a light on them. The light shows what is there, it does not create it. The great evil is already there and God's Word wants to eliminate those evils. It points them out, as it must, so that people might return to the right path." But instead of listening to the word, they attacked the one who spoke it - as they did to Jesus.

A Christian political leader elaborated further: "Romero testified that the Church must be the voice of the voiceless and the incessant defender of life. The Church must passionately pursue justice, but without identifying itself with any one particular party or any one particular ideology."

The controversy swirling around the figure of Romero continues to our day. During an interview given in 2007, Pope Benedict XVI explained, "The problem was that a political party wrongly wished to use him as their badge, as an emblematic figure. How can we shed light on his person in the right way and protect it from these attempts to exploit it? This is the problem." During a stop-over in El Salvador on Tuesday, President Barack Obama visited the slain Archbishop's tomb, while a week ago, the Salvador newspaper El Mundo quoted a politician's claim that "half of Salvadorans do not believe Romero is worthy of sanctification."

From the body of the Cathedral we went down to the vast crypt which has been tastefully arranged and decorated for liturgical celebrations. The first Bishop and three other Archbishops are interred, including Romero's predecessor and his successor. In a place of honour, we found the tomb of Archbishop Romero given special prominence. It is marked with a beautiful monument in bronze, more than life-size. It depicts the Servant of God lying in the sleep of the just, wearing his mitre and crosier by his side. The cloth covering his body represents the Word of God he served so well, and its four corners are held up by the four Evangelists. On the cloth lie a palm of martyrdom and several roses, and the body in repose gives the impression of rising.

As if in explanation, Archbishop Romero had said, "It is the Church's historical duty to lend its voice to Christ so that He may speak, its feet so that He may walk in today's world, its hands to build the kingdom, and to offer all its members 'to make up all that has still to be undergone by Christ.'"

We remained in silence and then we prayed. Nearly three years after the assassination, Pope John Paul II prayed there, too, and this is what he said: "Within these walls rest the mortal remains of Monseñor Oscar Arnulfo Romero, zealous Pastor. The love of God and service of his brothers and sisters led him to the very giving up of his life in a violent way, while he celebrated the Sacrifice of pardon and reconciliation."

Last December, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 24 March as the International Day for the Right to the Truth concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims. The purpose of the Day is to honour the memory of victims of gross and systematic human rights violations and promote the importance of the right to truth and justice; to pay tribute to those who have devoted their lives to, and lost their lives in, the struggle to promote and protect human rights for all; to recognize, in particular, the important work and values of Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero, of El Salvador, who was assassinated on 24 March 1980, after denouncing violations of the human rights of the most vulnerable populations and defending the principles of protecting lives, promoting human dignity and opposition to all forms of violence.

3. The House

Bishop Rosa Chávez then took us to visit the Divine Providence Hospital since on its grounds is the modest bungalow in which Archbishop Romero lived in the greatest simplicity. It is striking to see how little he had, including the second-hand car which he drove everywhere when visiting the parishes of his archdiocese. Here in his home, away from the many busy distractions of his office, is where Archbishop Romero dictated his daily diary and prepared his weekly sermon.

The first source was obviously Sacred Scripture to be meditated and assimilated and then applied. He worked hard on the preparation, using exegetical books. He did not make simplistic shortcuts between the Bible and the unfolding dramatic reality of El Salvador in the late 1970s. "I study the Word of God that is going to be read on Sunday. I look at my surroundings and at my people, and I illuminate these realities with this Word. I attempt to synthesize all of this so that I can communicate this Word to you and thus make this people a light to the world, so that they are guided by the criteria of the gospel and not by the criteria of the idols of this world. It is natural, therefore, that the idols and the idolaters of this world are disturbed by this Word, and so they have great interest in silencing and destroying and killing this Word." Pope Benedict XVI described him as a Pastor, full of love for God, fervently preaching the Gospel… Romero clarified that "the Bible alone is insufficient. It is necessary for the Church to take up the Bible and make it a Living Word again. Not in order to dole out psalms and parables word for word, but in order to apply it to the concrete situation in which the Word of God is preached at this time."

In addition to Sacred Scripture, he also availed himself of the whole body of what Catholics call the tradition. "In all he wrote and preached, Romero stood on the firm ground of the Church's doctrine, its deposit of faith, and its social teachings. He quoted Pope Paul VI often and referred repeatedly to the Vatican Council, to Medellín, and to Puebla. He said over and over that what he sought to do, simply, was to make real in the Archdiocese of San Salvador the teachings handed down through these important channels." He wanted to assure "that everything that the Second Vatican Council, the meetings of Puebla and Medellín, have wanted to promote, does not stay in the texts to be studied in a theoretical sense but rather that we live them and translate them in this conflictive reality so that we preach the Gospel as we should for our people."

In 1971, just after Romero was ordained as Auxiliary Bishop for the Archdiocese of San Salvador, Pope Paul VI marked the 80th anniversary of Rerum Novarum, not with another encyclical, but with the lighter format of an apostolic letter addressed to Maurice Cardinal Roy, the first President of Justice and Peace, whose fifth successor I am. The Pope begins with the reality: "In the face of such widely varying situations," he says, "it is difficult for us to utter a unified message and to put forward a solution which has universal validity. Such is not our ambition, nor is it our mission." It is not always easy to understand exactly what we as Church leaders are supposed to say and to propose - sometimes we generalize too much; at other times, we cqn get into details and practicalities which are really none of our business as Shepherds.

Then Pope Paul VI spells out with great clarity the biblical-ecclesial-social approach which underlies all Catholic Social Doctrine and its application to changing historical realities. "It is up to the Christian communities "to analyze with objectivity the situation which is proper to their own country", to be attentive to new problems emerging. We must first study them, we must learn to SEE them clearly and recognize what constitutes injustice at every level. "Seeing" demands more than a glance based on presumptions of ideology or prejudice or even political affiliation "to shed on it the light of the Gospel's unalterable words." Here we make use of biblical insight. Romero himself said that the Word of God, of which he was a humble servant, is like the light of the sun, which illuminates beautiful things but also things which we would rather not see.

These first two steps remind us of the advice given by the German Protestant pastor and theologian Karl Barth, "Prepare your Sunday sermon with one eye on the Bible and the other on the daily newspaper." But the Catholic approach also has a "third eye": "to draw principles of reflection, norms of judgment and directives for action from the social teaching of the Church."

This is the three-step method which Romero evidently learned "on the job" as Bishop of Santiago de Maria and even more as Archbishop of San Salvador, and I learned it in Cape Coast, too.

Pope Paul goes on to underline the dialogue which this method requires: "It is up to these Christian communities, with the help of the Holy Spirit, in communion with the bishops who hold responsibility and, in dialogue with other Christian brethren and all men of good will, to discern the options and commitments which are called for in order to bring about the social, political and economic changes seen in many cases to be urgently needed.

Therefore, "besides reading the Bible, which is the word of God," and the teachings of the Church, "a Christian who is faithful to the word must also read the signs of the times, the events, to illuminate them through the Word." The events in those years, both in the Salvadorian country and in the capital city of San Salvador, were confusing, tumultuous, often repressive and indeed violent, pitting citizens and soldiers against each other. "I ask the Lord during the week, while I gather the people's cries and the sorrow stemming from so much crime, the ignominy of so much violence, to give me the right words to console, to denounce, to call to repentance."

During his brief three years as Archbishop, Romero remained faithful to this method, as the homilies and his detailed diary make clear. He believed deeply that he was fulfilling his Christian vocation as Archbishop. The Sunday before he died, he declared: "Whatever might happen, whatever might be the will of God, His Word is not chained, as Saint Paul wrote. Even if I know that my Word keeps on being a cry in the desert, I know that the Church is trying very hard to accomplish her mission."

Each Sunday, then, Romero would spend more than an hour on theological themes, interpreting the readings from that week's liturgy, and delivering a message of reconciliation to a society bloodied and divided by violence. Fidelity to the Word of God, fidelity to the Church and her social and theological teaching, fidelity to his ministry in the name of the Good Shepherd, never failed Romero but brought him to the end. "The Word remains and this is great comfort for the one who preaches," he prophesied. "My voice may disappear, but my word, which is Christ, will remain in the hearts of those who want to keep it."

4. The Chapel

Bishop Rosa Chávez now took us to the Chapel where Archbishop Romero gave his life forever for his sheep. It too is located on the grounds of Divine Providence Hospital. While waiting for the door to be opened, the Bishop described exactly what happened on that Monday 24 March 1980. It was already evening, and, at sundown in the tropics, darkness comes quickly. Archbishop Romero was saying Mass. The assassin drove up to the main door of the chapel and, without alighting, took aim just as the Celebrant was raising the chalice at the offertory and praying: "…we have this wine to offer, fruit of the vine and work of human hands. It will become for us the cup of eternal salvation." Before he could finish the prayer, a single shot rang out and Archbishop Romero slumped to the floor at the altar.

The next day, Pope John Paul II vigorously denounced the foul deed: Archbishop Romero was "assassinated in barbarian fashion while celebrating the Holy Eucharist, shot at the most sacred moment, during his highest and most divine function." From the rite of ordaining a bishop, the words come back: "Always be mindful of the Good Shepherd … who did not hesitate to lay down his life for them."

We entered the Chapel in silence and went up to the altar, we knelt and prayed. Noticing how the Chapel is laid out, one clearly concludes that it must have been a professional hit-man to pull the trigger from outside the door, aiming at the Archbishop's heart, probably without being noticed because the chapel was brightly lit but outside it was already dark. "At this special moment of dismay and trepidation," Pope John Paul II continued, "I invite you to join in my pain and in my prayer …We are left speechless in front of such violence which would not even stop at the door of a church in carrying out its blind programme of death. Dearest brothers and sisters, please let the Pope express all his sorrow at this latest episode of cruelty, infamy, ferocity. A man has been killed, and he joins the much too long array of innocent victims; a Bishop of God's Church has been killed, while exercising his sanctifying mission in the offering of the Eucharist. In this way he crowned with blood his ministry that was especially concerned with the poorest and most marginalized. It was a supreme witness that has provided a symbol of the torment of the people, but also a cause to hope for a better future."

On Romero's anniversary twenty-seven years later, Pope Benedict XVI spoke of all the bishops, priests, religious and lay Christian struck down while carrying out their mission of evangelization and human promotion: "These missionary martyrs … are the 'hope of the world', because they bear witness that Christ's love is stronger than violence and hatred. They did not seek martyrdom, but they were ready to give their lives in order to remain faithful to the Gospel. Christian martyrdom is only justified when it is a supreme act of love for God and our brethren." And six weeks later, the Holy Father added, "Archbishop Romero was certainly an important witness of the faith, a man of great Christian virtue who worked for peace and against the dictatorship, and was assassinated while celebrating Mass. Consequently, his death was truly 'credible', a witness of faith." And a witness, in Greek, is martyr.

Conclusion

Now that we have spoken of Archbishop Romero's mission, his pastoral ministry and his martyr's death, let me go back to an important detail on his tomb. There, above his name and his brief dates as Archbishop from 1977 to 1980, are the four words of his motto: Sentir con la Iglesia. The word sentir means many dimensions of our human existence: to see things as the Church sees them, to suffer as the Church suffers, to feel things as the Church feels them, finally to judge and decide and act in the light of the Church's teaching - not an ideal or perfect Church, but the Church as it is, from diocese to diocese including Rome. With reference to the Mystical Body, Archbishop Rowan Williams explains Romero's Sentir con la Iglesia as "more and more clearly, sharing the agony of Christ's Body, the Body that was being oppressed, raped, abused and crucified over and over again by one of the most ruthless governments in the western hemisphere." In the homily for Good Shepherd Sunday on which we have been meditating, Archbishop Romero articulated the daunting challenges of our faith as we, too, encounter them. He encouraged us to be grateful and faithful and responsible: "Thanks to God, we are Christians and we believe in the Good Shepherd. And then what? We have a personal responsibility. The Good Shepherd who is presented to us in today's three readings is a pastor who calls us to collaborate." So we make "our prayers to the Good Shepherd. We pray that his courageous and guiding presence might continue to be revealed in the world through the voice of his pastors."

For me, drawing near to Archbishop Romero and meditating on his sermon about the Good Shepherd, I feel encouraged in my role as as President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and a close-co-worker of the Holy Father. Romero was a good Shepherd who led from ahead and from behind, who prayed and reflected and taught, who lamented and denounced and dialogued, who encouraged the weak and pleaded with the powerful. He has given me much to take back to Rome with me, and I trust that he leaves much for you in the Church of the United States and at the University of Notre Dame. As he made his own the social approach developed by the Church since the time of Pope Leo XIII, I humbly suggest that you also make it your own in your Christian life and in all the departments of this great Catholic University. For this purpose, please listen to the three steps again:

"to analyze your situation with objectivity", with the best of the human and social sciences "to shed on it the light of the Gospel's unalterable words," whose "inspiration, enriched by the living experience of Christian tradition over the centuries, remains ever new for converting men and for advancing the life of society" "to draw principles of reflection, norms of judgment and directives for action from the social teaching of the Church."

Let us pray that God, who called Oscar Arnulfo Romero to be a good Shepherd in his Church and guided his feet along the difficult path of justice and reconciliation, may make the living memory of this Martyr Bishop fruitful in our own lives as Church and as University.