HOUND: Visions in the Life of the Poet Francis Thompson

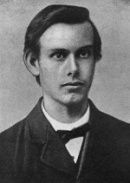

Francis Thompson

HOUND: Visions in the Life of the Poet Francis Thompson

Written and directed by Chris Ward

The Catholic poet Francis Thompson (1859-1907) is best known for his poem ‘The Hound of Heaven’ which records the pursuit of the human soul by God:

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the mist of tears

I hid from Him.

Thompson had attended the seminary at Ushaw College, seemingly destined for the priesthood, but was expelled due to his ‘natural indolence’. He proceeded to study medicine but failed his medical exams three times. He was disowned by his family, failed at several (mostly unskilled and menial) jobs, and an opium habit grew into a destructive addiction. Thompson ended up destitute on the streets in London.

Two significant interventions we know about succeeded in prolonging his relatively short and frail existence. A mysterious prostitute, whom Thompson described as his ‘saviour’, shared her income, her lodgings and her love with him (this was the subject of an excellent Radio 4 play some years back, the title of which escapes me).

Secondly, during all this adversity, Thompson was composing and writing poems. After his death, G.K. Chesterton remarked that the country had lost the ‘greatest poetic energy since Browning’. Thompson sent a sample of his poetry to the periodical Merry England which was edited and published by the Catholic couple, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell (who went on to be a prominent suffragist and anti-colonialist). The Meynells evidently shared Chesterton’s high regard for Thompson’s work. They sought out the vagrant poet, championed him, invited him into their home and arranged for him to spend time with the Norbertine Canons in Storrington, West Sussex.

Yet Thompson’s addiction always lurked. His frail constitution eventually succumbed to tuberculosis and he died in 1907 at the age of 48. His reputation as a poet seemed to be at its height at this moment. Within three years, a free-standing edition of ‘The Hound of Heaven’ had sold 50,000 copies.

The poem’s vivid language, its imagery, its inexorable rhythm, and its ever-restless wrestling with the demands of the gift of faith continue to strike a most powerful chord and make it a beloved work. It has even been cited in the Supreme Court of the United States of America.

Chris Ward’s play covers most of the above biography, charting Thompson’s life from 1897 until his death, 20 years later.

The decision to stage the play in churches is an excellent one. I saw the Wet Paint Theatre production in St Giles-in-the-Fields, London WC2, last weekend and the sacred space added much to the subject matter and to the overall ambience of passion, vision and mysticism. Ward had previously collaborated with Derek Jarman who, I feel, would have applauded several of the artistic tableaux created, and the eclectic mix of high and low art, camp and exquisite pathos, the sacred and the profane.

Such artistic juxtapositions came together for example in a scene set, metatheatrically, inside a church. Francis kneels at the foot of a statue of the Virgin and says: ‘We adore you O God and we bless you, for by your holy cross you have redeemed the world.’ Meanwhile, his prostitute ‘saviour’ is receiving a knee-trembler outside (buttocks displayed here the precursor to other nudity in the piece) and another low-life companion is robbing the collection box. Left deserted in the church, a spiritually and physically starving Francis calls out to receive succour from the Madonna’s ‘breasts of tenderness’. The statue moves, opening her blue gown to allow the poet to suckle her, covering him under her protecting veil.

This moment called to mind the lactation of St Bernard. It also happened to take place directly underneath a gold-leaf altar carving of the ‘kind life-giving Pelican [an emblem of Christ], repasting its offspring with its blood’ (to paraphrase Hamlet) – thus creating a highly felicitous and related iconographic shadowing.

Directly above the Pelican and the high altar, a stained-glass window depicted Christ surrounded by Moses and Elijah and three cowering apostles, in a rendering of the Transfiguration, along with God’s words: ‘This is my beloved son in whom I am well pleased. Hear ye him.’

It is Ward’s avowed intention to present ‘an extraordinary spectacle of visionary images both verbal and visual … in a hallucinatory poetic interpretation of Francis Thompson’s beautiful and tortured mind and soul.’

The play certainly contains much transfiguration of reality and the Transfiguration window also chimes with Thompson’s self-fashioning of himself as a prophet. However, while the script contains crisp dialogue and heightened moments, I regret that more of Thompson’s poetry was not used in a more prominent way. We did not hear the Poet enough. As Thompson, Hugo Harrison looked every inch a Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood waif but I longed for some poetic diction and deeper soul.

The production however, remained highly absorbing, not least thanks to Ward’s scenographic and artistic sense, his rich and varied musical scoring (eg Gilbert and Sullivan, ‘Stranger in Paradise’ from Kismet), and some fine performances from the ensemble of young actors.

Niamh Callan was excellent both as the compassionate Saviour prostitute ‘Little Flower’ and as one of the Meynell children; Luke Thomas was most amusing as the hearty guardsman who seeks out a bout of nude Graeco-Roman wrestling with Thompson, and Alyssa Cox’s singing added great dynamism and emotional depth to several scenes.

Ward’s comic touches are generally fine (Franck Jeuffroy’s Mr Bumptious strikes some lovely balletic poses) though some might question the balancing of the tone in the presentation of a caped Jack the Ripper (denizen of the Victorian melodrama) and his brutal murdering and evisceration of Little Flower. Although the use of red ribbon to portray such deaths is now highly familiar, I thought it worked very well here. Interestingly, Thompson himself is on the long list of Ripper subjects, hence no doubt the interpolation. The voice-over describing the state of a ripper victim was highly upsetting.

Ward demonstrates his own knowledge of religious art and iconography in further memorable tableaux: Little Flower drying Thompson’s feet with her hair; the poet prone with all his ribs showing, as in the Lamentation; a scourging scene as of El Greco, and a hallucinatory Crucifixion of the poet surrounded by strange masked figures which reminded me both of carnival and Bosch.

As red roses were scattered over the dead poet, to be sought in the ‘nurseries of Heaven’, I thought to myself that Ward needed to seek out still further the poet’s voice and develop further this fine creative undertaking.

Hound is on at St Olave’s Church, 8 Hart St, London, EC3R 7NB, 8-10 May at 8pm

Dr Philip Crispin is a lecturer in Drama at the University of Hull.