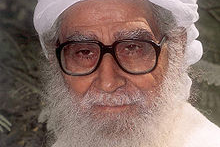

India: Christian-Muslim conversation - Dr Victor Edwin SJ interviews Mujeeb Kinaloor

Mujeeb Rahman Kinaloor

Dr Fr Victor Edwin SJ Lecturer on Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations at the Vidyajyoti College of Theology, New Delhi interviewed Mujeeb Rahman Kinaloor, a renowned Muslim cultural activist in Kerala who is a writer, lecturer, columnist and teacher. He was a leader in the student and youth wing of the Mujahid movement, a leading reformist movement in Kerala, for 25 years. Now he writes freely and is not part of any religious organization and engages in cultural activities. He has published more than a dozen books and has been the editor of many Muslim publications.

Q: Could you please share something about yourself?

I was born in 1972, in a middle-class family from a small village called Kinalur, which is in the Kozhikode district in northern Kerala. My father was a construction worker and my mother a housewife.

I completed my schooling from a nearby government school. I then enrolled as a private candidate for a pre-degree course. I graduated from Calicut University in Arabic and obtained a postgraduate degree in Arabic literature from Aligarh Muslim University. I also obtained a BEd in Arabic language teaching.

After I finished my formal studies, I worked in some newspapers for a while. After that, I was appointed as an Arabic teacher in a government high school. Later, I took leave and turned to journalism, but now I continue to teach in a school.

Q: Did the neighbourhood where you were brought up have people from different religious backgrounds, or was it largely people from a single religious community?

My village consists of Muslims and Hindus. As far as I know, there have never been any communal riots or clashes in or around the village. Although there are various political parties and community organisations that are active in the village, there is a friendly atmosphere there. Since childhood we had Hindu neighbours, belonging to different castes. We had good relations with them. As a child, I never felt any alienation in the name of religion. My memory is of a loving neighbourhood, where people shared their joys and sorrows with each other.

Q: Growing up, did you have any friends from other religious backgrounds? If so, how do you think this impacted on your understanding of other religions and their followers?

Many of my childhood friends were from Hindu families. Going to school, sitting in class and playing in the evenings were all things we did together. I did not experience any discrimination or sense of otherness then.

When I was a child, there was a library near our house - it still exists. It was a secular platform for children. It brought together children from different religious and caste backgrounds. I borrowed and read lots of books from the library. Along with other children from the area, I was an active participant in the art and cultural activities that were held in the library.

It was at that time that I first acted in a drama. The play was part of the annual celebration at the primary school I attended. Interestingly, my role was that of a middle-aged Brahmin man.

Q: Many children are socialised into imbibing certain negative stereotypes about other religions and their adherents. Was this the case with you too, when you were young?

As a child, I did not experience any discrimination in the name of religion. There was a small degree of caste-based segregation among Hindus at that time, but there was not even that much segregation in the name of religion. Most of the teachers who taught me when I was little were not Muslims, and they all loved me and encouraged me.

Q: How were your parents' relations with people of other faiths?

Many of my father's closest friends were Hindus. He was not a religious man. He regularly read newspapers and was interested in politics. He was a socialist-leftist. But among his friends were people with other political views, including some who believed in Hindutva politics. Talking to them, meeting them and visiting their homes were part of his routine. He used to invite his friends over for festive occasions and special receptions at our house. Similarly, during festivals like Onam and Vishu and for wedding ceremonies, we used to go to their houses. They all loved me very much.

Q: Is there something particularly striking in what you remember of how your family members related to people of other faiths which might have played some role in inspiring you later to be concerned with trying to promote inter-community understanding and harmony?

My grandmother was a well-read woman. She remained in contact with her Hindu women friends till her death. They used to see each other from time to time. They would help each other when faced with financial difficulties. If they had no money, they would pawn their gold jewellery to help each other. They all had a great love for me. I grew up seeing that love and friendship. When I passed the SSLC (Secondary School Leaving Certificate) examination, the first person to give me sweets and compliment and encourage me was a Hindu woman neighbour of ours whom I would address as 'Amma' or 'Mother'.

My mother's uncle had a small shop that sold vegetables and stationery. During my school days, I would sometimes go to the shop and help him out. Most of his customers were not Muslims. He maintained a relationship with them that went beyond buying and selling. At that time, all such affairs, whether trade or wage-labour or whatever, were based on love and care. Human values were the basis of all relationships.

During the Onam festival and Diwali, my uncle had a tradition of giving gifts to his customers. He gave them sweets, vegetables and fruits as gifts. I remember going with him to give presents to his client friends. What wonderful customs there were those days in the villages to maintain loving friendships!

Q: Please share some significant events in your childhood involving people of other faiths which may have had a major impact on your way of relating to them.

Back then, there was a mechanism in the villages for villagers to help each other in times of financial hardship. This was a kind of chit fund, which was known as 'Tea Party' (locally, it was called Payat). When a villager was in financial difficulty, he would invite other local people over with a special invitation letter. People would respond to his invitation, and there would be a small tea party either in the person's home or in a nearby tea shop. Guests would contribute as much money as they wanted to, and a cashier would record the amount they that they had given. Those who collected money through Payat would later return a larger amount than the amount they had received to the donor when the latter's turn came. When a person died, his children or other heirs would take over, and so it would continue to be a network. Apart from being an interest-free loan transaction, Payat was a system that fostered social trust, friendship and compassion among people. It helped to people to socially interact, renew their relationships and keep local connections secure. Local practices like these made interfaith or inter-community relations at the interpersonal level most beautiful and, at the same time, unpretentious.

In the old days, if there was a wedding party or reception in any village house, neighbours and friends - no matter what their religion - would be there to help prepare the tent and make the food and distribute it. A noble culture of interaction bringing together people from different religious backgrounds was the basis of rural life in the region where I grew up.

Q: How do you recall relations between Muslims and others in your area when you were a child, and how do you see them now? If these relations have changed, in what way do you think they have and what do you think may be the cause(s).

The last half century has seen enormous changes. Almost all of the above experiences have become myths. There are many reasons for this. One of the main reasons is the lack of poverty in the villages now. Migration to Gulf countries has vastly changed the living conditions of villages in much of Kerala. With the advent of modern capitalist culture and rapid urbanization, all aspects of life were institutionalized. Professional service-providers entered spheres which were earlier governed by local practices that brought people together in interpersonal relationships based on mutual assistance. Changes in politics also played an important role in this regard. The demolition of the Babri Masjid caused concern among Muslims, and it led them to communal narrow-mindedness. It should also be mentioned that new trends of religious fundamentalism began to spread among different religious communities, negatively impacting on inter-communal relations.

So, things today are very different from back when I was a child.

Q: Please share something about your academic training in Islamic Studies.

After finishing high school, I joined a pre-degree course as a private candidate. My subject was Commerce. At that time, I was also active in the student wing of a religious organisation based in Kerala that promotes a kind of moderate Islam among Muslims. At this time, I became interested in Islamic Studies, and so I wanted to study Arabic. I went on to study Arabic and Islam for five years in Rouzhathul Uloom Arabic College, in Feroke, which is affiliated to Calicut University. Although it was a university degree course, the institution that offered the course was an Arabic College, which was like a Muslim seminary in some ways. I took up residence in a college hostel, which was run by the same institute. Those who stayed in the hostel were all Muslims. Naturally, then, all my classmates and teachers were also only Muslims.

As I left home for the hostel, the friendships I had back home diminished. When I came home for holidays, I would be active in religious activities. My only area of interest then was conducting various activities in mosque related to religious preaching. At the same time, while at college, I gained opportunities for developing writing and leadership skills. I was elected to top positions of our organisation's students' movement. I began writing for the organisation's publications. This period gave me many opportunities for personal growth.

Subjects I had to study in the Arabic College included the Qur'an, Hadith, Arabic Language and Literature, and Islamic History and Philosophy. Institutions like our college were designed to create religious preachers and educators. The students who came out of such institutions had an anti-priestly and anti-orthodox attitude. But they were also taught that the Qur'an and the life course of the Prophet alone were the solution to all the problems facing the world. These seminaries taught that liberation in this world and in the Hereafter is possible only if and when one becomes a believer in Islam in the fullest sense, as they understood it.

: Please describe the sort of issues that you have been writing on. Which papers have you been writing for? Have you also written on the need for Muslims to engage in interfaith dialogue and understanding? If so, could you please share something about that?

I have been writing for various magazines since I was a college student. Most of my early writings focused on Islamic faith, Muslim history, and socio-political issues of the contemporary Muslim world.

My first published article was a critical study when I was just 18. At that time I was reading the Malayalam translation of the book Liberation Theology in Islam by the late Asghar Ali Engineer, a prominent Muslim intellectual. When I read the book, I thought it was a Marxian interpretation of Islam.I prepared a critical study of the book and sent it to Shabab Weekly, a Malayalam Muslim magazine. The title I gave the article was 'Misconceptions in Liberation Theology' and it was published in the magazine. Interestingly, I later re-read the same book as well as other books by Engineer and I became his sympathiser! I had a relationship with him for some ten years. I had the chance to meet him many times, in different places, and we had many conversations. Once, when I told him about the critical article that I had written against him when I was young, he laughed out loud!

Starting in 1993, shortly after I graduated from college, I began working as the editor of a Malayalam children's magazine called Balakauthukam (the word roughly translates as 'Wonders for Children'). It was not an Islamic publication as such, but its aim was to inculcate values in children from an Islamic perspective. It contained folk stories, life stories of great people, poems and illustrated tales. It contained rich teachings from other religions too that sought to inculcate harmony and friendship in children. Muslims were not the only writers and illustrators for the magazine. The works of prominent Malayalam children's writers from other religious backgrounds too were regularly published in it. The magazine's pre-press work, graphics and printing were routinely outsourced. That helped me to connect with people of other faith backgrounds. I recognise it as an added bonus to have been able to make a lot of friends from different religious backgrounds.

In 1997, the management of Balakauthukam launched another Malayalam magazine, called Sargavicharam ('Creative Thoughts). I had edit it too along with Balakauthukam. It was a magazine for college students. Sargavicharam focused on issues related to education, cultural issues related to college campuses, art and literature, stories and poems. It also published simple articles on Islamic values and culture. It provided opportunities for writers and students of all faiths and political views. The magazine was also an experiment in exploring whether a multicultural publication was possible on a religious basis. As such, it was successful, but it lasted only for some three years.

After that, I worked for a long time for the Islamic magazine Shabab ('Youth') and the family magazine Pudava (the word here denotes the 'cultural costume' of the family). Thereafter, I joined Varthamanam, a completely secular daily newspaper. It was published by a Muslim group and was based on social justice and secular values and a commitment to inter-community harmony. The majority of the editorial board, including its editor-in-chief, were not Muslims. It lasted for around ten years.

Shabab and Pudava are still alive. I still write for them regularly and provide advice to their editorial board for preparing topics for every issue. Despite being Islamic publications, they have, to a certain extent, been able to maintain a broader perspective on content and approach as publications operating in a pluralistic society. Issues faced by Muslims as a minority, challenges facing Indian secularism in general, environmental issues and contemporary changes in the world are among the topics covered in Shabab. It regularly publishes articles and translations by prominent writers, not only Muslims but also other people of other faith backgrounds and even people who do not believe in any religion. At the same time, reflections on Islamic beliefs, customs and culture are, of course, part of Shabab's content. Pudava's content includes issues related to marriage, family, health, agriculture, food, travel, art and music, along with Islamic themes. Many people from different religious backgrounds write in this magazine.

An important part of my life has been spent on the activities of these publications. In addition to having written hundreds of articles in them, I have been able to play a crucial role in shaping their editorial policies and topics. As far as I know, there don't seem to be any other Muslim publications in India that share their style and approach.

Q: Besides writing, have you engaged in any other form of work for interfaith understanding and inter-community harmony?

In terms of religious harmony, it is a fact that Kerala is a model state in India. There is a long historical tradition behind this. The Muslim Arabs who came to Malabar for trade centuries ago were received with great respect by the Hindu kings of Calicut, who gave them all support. The Hindu Zamorin kings married local women to the Arabs and facilitated the construction of mosques for the Muslims' worship. The Muslims became loyal navigators of the Zamorin kings. This is documented authorized history.

I think an important way to maintain religious harmony in Kerala is to constantly remember this great heritage. For love and friendship to prevail between communities, it is important that the members of the communities be loyal and honest. The reason why the ancient Hindus were ready to accept the Muslim Arabs as trading partners was the latter's loyalty. This is something that Muslims of Kerala today need to recall. They need to evaluate whether they can maintain the loyalty and honesty of their ancestors in social relations and dealings with others. And the Hindus of Kerala must examine themselves to see if they can relate with the Muslims without any biased thinking, just as the Zamorins did.

I have had the opportunity of organising many history seminars and speaking at such functions on the relationship between Hindus and Muslims in Malabar, the part of Kerala where I live. My little book in Malayalam whose title translates as Religious Harmony and Muslims of Kerala describes this historical experience of Hindu-Muslim brotherhood.

Creating opportunities for people of different faiths to get to know each other is very important in social life. I remember setting up open galleries in our village for Hindus to watch Eid prayers. On these occasions, we invited our Hindu friends to the venue, distributed sweets to them and greeted them. Similarly, in my youth, under the auspices of some cultural organisations of the area, various arts and sports competitions were organised during Onam and Vishu celebrations in which everyone in the village, irrespective of religion, participated. But now such things are not happening.

Q: Have you studied religions other than Islam?

I have read some books on Hindu and Christian religions and have also talked with scholars of those religions. I have not studied any other religion in depth or authentically. When I was a student, I read some books written by Muslim scholars comparing and critiquing religions other than Islam. But later, I realised that each religion has its own reasons to exist.

Q: There are two very different ways of seeking to address issues of inter-community conflict and inter-community harmony. One is to seek to critique, oppose, denounce and combat what is called 'communalism'. Another, very different, approach, seeks to promote inter-community bridge-building and understanding through inner transformation and positive interpersonal interaction.

As a means for seeking to improve inter-community relations, how do you look at these two distinct approaches? Which of these do you think is more effective in changing people's hearts, transforming their minds and promoting genuine regard and respect for people from diverse faith backgrounds?

Communalism is a deadly virus that wreaks havoc on society. Communalism is not compatible with the core values of religions. Therefore, communalism must be resisted by religious people themselves. In my opinion, for this purpose, secular groups should be formed and people of all religions should work together in such groups to promote inter-community harmony. There should be plenty of political and cultural platforms to foster such harmony. Many people have turned to communalism, for a variety of reasons. We need to oppose communalism without seeing individuals who may be communal in their thinking as enemies. Being closer to human beings and loving them without prejudice or conditions can make a big difference even to those who are presently communal in their thinking.

Q: Could you please reflect on the role of personal friendships and other such close relationships between individuals from different faith backgrounds in helping dissolve prejudices and bring people close together?

I am someone who values personal relationships. I do not hesitate to make friends with people of any ideology. Most people become religious by birth, not by choice. There will be good and bad people in every religious community. So, my stand is that no one should be excluded from one's friendship on the basis of religion or ideology.

Let me share an experience of mine. In general, Muslims have a negative attitude towards befriending Jews. There is a perception among Muslims that the Jews are corrupt. Years ago, I met a woman called Dominique Sila-Khan, a renowned academic who studied common values between various religions. She was a European woman of Jewish background who had married a Muslim from India. I once visited her house in Jaipur. We discussed many topics, over a long conversation. At the insistence of her husband and her, I spent a night at their house. My friendship with them taught me a great lesson. If we can get closer to other people personally, the walls of preconceptions and misconceptions will crumble.

Votaries of religions often have a tendency to be hostile not only to different religions but also to other sects of the same religion. For instance, many Sunni Muslims consider Shia Muslims to be heretics and adversaries. Many Shias view Sunnis in the same way. Many people may bitterly hate members of rival sects of the same religion but at the same time have friendly relations with people from other religions!

My two visits to Iran made a big impact on my thinking on this matter. Most Iranians are Shias, and I come from a Sunni background. When I went to Iran, I met some really good people who were Shias. I even spent some nights at a Shia home. Those people were very kind to me.

Such personal interactions between members of different sects or religions can work wonders in dissolving walls built on prejudice in a manner that no amount of lecturing possibly can.

Q: Do you have friends or relatives from religious backgrounds other than Muslim?

As mentioned earlier, I have had many non-Muslim friends since I was young. But it is a fact that during my later formal education and then during my active engagement in religious activities, those relationships got diminished. There were no non-Muslims among my so-called soul mates in this period. But this was not something that happened deliberately. It came about by chance. But now I have very close non-Muslim friends. And they include not only religious believers but also some who do not believe in any religion. I can get along well with them.

There is no doubt that my friendship with people of different ideologies has greatly influenced my views. I do not care what they believe or do not believe. I do not think that I must convert them to my faith. I think my conversations with them have freed me from ideological narrow-mindedness.

Q: Coming back to your childhood, could you share something about the way religion was understood and practiced in your family then? How did you relate to this sort of religiosity? What changes, if any, do you see in your way of understanding or practicing religion over time?

If you ask me if my attitude towards religion has changed, of course it has. I can now think differently from many traditional believers who see religion, customs, and practices purely mechanically. I try to read religion rationally, instead of following religion literally. I think the inner essence of religious texts and laws is important. The values contained therein are more relevant than the framework itself.

Q: Do you presently identify yourself with any particular religion? If yes, how do you think your understanding of this religion might be different from how it is conventionally understood?

I am a Muslim. Even when I say 'Muslim', I must explain that I do not agree with the orthodox superstitions and blind customs that exist in the name of Islam. It is a fact that most human beings are culturally associated with some or the other religion. Humans cannot live without cultural roots. Culturally, what I can most relate to is Islam. As the religion into which I was born and in which I was raised, it has become ingrained in my identity. In today's world, I think the declaration of "I am a Muslim" is a very important statement politically too. Being a Muslim today is a very challenging thing. Right-wing politics have gained strength in all parts of the world, and they are using Islamophobia extensively to make Muslims apologetic. Therefore, it is a political duty to stand for justice at a time when Muslims are being discriminated against. At the same time, one must be critical of and oppose wrongs that Muslims do, including in the name of Islam.

Q: There are multiple religions, and each religion has its unique belief system and associated rituals. Each religion, as conventionally understood, makes its own unique truth claims. Given this, it is hardly surprising that competition, and even conflict, has been endemic between diverse groups of religionists.

In the light of this, how do you think people who claim to follow this or that religion can live together in harmony despite their religious differences, and, beyond that, can seek to learn and benefit from each other and their faiths? Could you please reflect on this in the light of your personal experience?

The material world is extremely diverse, and diversity is intrinsic to the beauty of the universe. Similarly, the world of ideas is made beautiful by diversity. Everyone is free to believe that their religion or ideology is right. Just as I think my own beliefs and ideas are right for myself, I need to give my friends the freedom to believe in their beliefs and ideas. Then, I do not have to argue and confirm my correctness. I do not need to impose my faith on others. Every religious person can live in harmony with others while being themselves. They can help each other at the same time as they choose to believe in this or that ideology. Adherents of different religions need to be able to live in harmony with each other. Every religion should teach its followers that.

The Holy Qur'an says: "Indeed, We have honoured the children of Adam" (17:70). This sentence means that God has respected all human beings, regardless of their religion, nationality, color or gender. That being the case, one has no right to disrespect those whom God respects.

It is a fact that there are differences of opinion between religions on many issues. Those differences cannot be eliminated through disputes. While these differences may continue to exist, the fact is that there is complete harmony between religions on a number of other issues. Many problems on Earth can be solved if believers unite on common grounds.

Humanity is facing many crises. Many personal and social conflicts make human life unbearable. Many common crises plague us, such as poverty, disease, unemployment and environmental issues. We need to work together to find a solution to such problems, regardless of what religion, caste or ethnic group we may identify with. Religious harmony is not a mechanical action, but, rather, the result of various processes. Human beings must live and work together with love and compassion, and then inter-religious relations will naturally improve.

Let me cite an instance. There have been two major floods in Kerala in the last two years. On these occasions, people worked together in rescue operations without being impelled by divisive biases based on religious identity. Hindu temples were cleaned by Muslim youth. Churches were opened for Muslims to pray in. When some Christians died in the floods, their bodies could not be taken to the hospital as the road was blocked, and their postmortem was arranged in a nearby mosque. Many such models of inter-community solidarity made headlines. These experiences show us some natural ways to achieve oneness among human beings who may believe in different religions.

Q: There are many individuals and NGOs in India that are working on a range of social causes. But the number of individuals and organisations working for promoting interfaith understanding and inter-communal harmony is very limited. Why do you think this is the case?

NGOs must be inclusive of people of different religions, both in terms of their staff or activists and their beneficiaries. Instead of a particular religious sect working for the welfare of their own people, we should work for all vulnerable human beings equally. The goal of all welfare and charitable activities should be human service. They should not be used for religious propaganda.

We need to consciously create opportunities for people from different faiths to understand each other-for instance, workshops for children and youth from different religious backgrounds to stay together and get to know each other, gatherings of families of different religions, interfaith journeys, etc.

Q: There are relatively few Indian Muslim groups who are actively engaged in promoting inter-community harmony and interfaith understanding. Why do you think this is the case?

Muslim religious organizations generally approach interfaith dialogue as a religious propaganda programme. Sometimes, even discussions intended to dispel misconceptions between religions end up being divisive. It does not augur well for interfaith relations when an attitude of arguing and winning prevails. I believe close inter-personal relationships between people from different faith backgrounds, and not organised debates, are the effective way to improve interfaith relations.

Q: What do you see as the purpose of human life, and how do you think working for better relations between people from diverse faith backgrounds might fit into this purpose?

For me, there is no greater goal than to do the best I can for other people and for the world in general. I want to live without hurting others, even if I can't do much good. Likewise, I want to be able to accept others as they are. I believe that true spirituality is to love all human beings, to do justice to them and not to hate anyone.