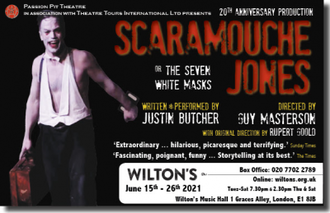

Scaramouche Jones Review

I am hard-pressed to imagine a more joyful return to the theatre after the doldrums of Covid confinement than a trip to Wilton's Music Hall to see Justin Butcher perform in his celebrated tour de force Scaramouche Jones. An historic venue for an historic occasion: this is the twentieth anniversary production of the play, penned on the eve of the Millennium and which originally starred the late, great Pete Postlethwaite in its first fully fledged outing.

The one-man play is a form of meditation on the state of the world at the end of the Twentieth Century - and yet all its central preoccupations remain all too relevant today.

The hundred year-old clown Scaramouche Jones has just given his final performance on Millennium Eve and proceeds to recount his story (and history) to the assembled audience.

And what a picaresque story it is. Our hero is born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, during carnival on the cusp of the Twentieth Century, the son of a dark-skinned gypsy prostitute and, apparently, an Englishman - for Scaramouche is remarkably white. To deliver just a few headlines: his mother is murdered and he is sold into slavery. After some sea-faring, he accompanies his master, an anglophile snake-charmer, to Haile Selassie's coronation in Addis Ababa. Disaster strikes when their prize cobra disrupts the ceremony but Scaramouche is freed from prison by a lecherous Italian dignitary from whom he escapes by diving into the icy waters in Venice harbour. Here he is revived by fellow gypsies and ends up rescuing one of their young daughters from incarceration. Brutally beaten, he finds refugee in a Polish monastery and is joined by several others who are seeking a safe haven from Nazi atrocities. As war erupts, he flees once more, is captured, and forced to become the grave-digger in a concentration camp in Croatia. Here, he manages by silent clowning to diminish the suffering of child victims in the camp. This leads to his exoneration and the offer of a British passport and an ironic homecoming: 'For he is the son of an Englishman.'

Scaramouche Jones resonates with many sources, not least parodic echoes of imperialist derring-do as recounted by John Buchan, Conan Doyle, Haggard and Kipling. The play's examination of empire, race and identity remains all too topical given the baleful culture wars being weaponised by the right.

Arrestingly, a crucifix stands over all, centre stage, and overarching all, it is possible to glean a fascinating Christian ethos sustaining the drama and Butcher's vision.

On several occasions, the protagonist Scaramouche declares his name is 'legion' (like the Gadarene demoniac). He represents the innumerable 'wretched of the earth', the voiceless, against whom terrible deeds are done. Ironically, in the face of all the world's suffering in the twentieth century and all the seeming inanity, he had opted for silence some 49 years earlier, at the Festival of Britain.

Now, just prior to giving up the ghost on his hundredth birthday, he opts to tell his story. This story-telling is both an unburdening and an act of agency. The mute master of pantomime is in all truth a supreme verbal artificer.

Scaramouche Jones speaks up for all the voiceless. At seven crisis points in the narrative, he identifies a white mask which settled over his face, a certain attitude or expression indicative of the state of his soul. That number seven has deep resonance of course: the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit; the seven joys and seven sorrows of Mary.

With the sharing of his story, Jones unburdens himself and is able to slough off the debilitating masks. He is a representative everyman figure, an anti-hero, risible in the eyes of the powerful but full of empathy and grace.

Clowns are predominantly associated with comedy but there are of course sad clowns and clowns are often abject failures, open to taunts. The twin masks of theatre, of tragedy and comedy, apply to Scaramouche Jones. Christ too was both 'a tragic actor born' and portrayed as a fool, all clad in white, when mocked and beaten in the passion pageants of the mystery plays. St Francis of Assisi too was known as 'God's Jester'.

Like Christ and St Francis, the protagonist here is full of love and empathy for those suffering, most notably the soon to be exterminated children in the death camps. In his compassionate pantomime he enacts for them, he ends by metamorphosing into a fluttering angel. 'Flights of angels sing you to your rest.' Even as the lighting makes him look like a death's head, he evokes the never-extinguished hope of the Requiem Mass, present too at the end of Hamlet (a play full of Catholic maimed rites), that death is not the end, but that those suffering will rise in glory, finding a true home in Heaven. And in a further nod to the clown-prince Hamlet, he has told the children's (and his Scaramouche Jones's) story.

Butcher has triumphantly carried forward the baton for Erasmus's Mask of Folly (itself a punning homage to St Thomas More with its Latin title Morae Encomium) in which vicious human folly is gathered up into an all-compassionate divine folly of wisdom and virtue.

Everything comes together in a superb production, beautifully directed by Guy Masterson. Damian Hale's sensitive video design is mercifully unintrusive and complements Butcher's beautiful verbal picture-painting. The overshadowing of the afflicted seven white masks was particularly well done.

Finally, Butcher's physical, gestural acting and clowning are on a par with his excellent multi-voiced verbal delivery. His Scaramouche Jones is a holy fool who ends his story by blowing out a candle in a tableau worthy of Georges de la Tour. 'Out brief candle.' His life is over. The motley has shuffled off this mortal coil. But we are left dazzled and transfigured by such humanity.

To book tickets for the remaining performances (tonight at 7.30pm and tomorrow at 3pm and 7.30pm), visit: www.wiltons.org.uk