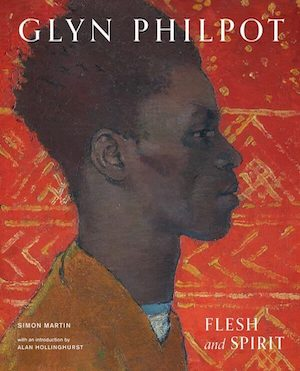

Chichester: Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit

Image: Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

When I was in my teens, I was very fond of a flamboyant portrait of the actor Glen Byam Shaw as Laertes. So I was delighted to be reunited with it as a representative example of Glyn Philpot's 'swagger portraiture' in this superb exhibition dedicated to the artist at the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester.

As the 'Flesh and Spirit' of the exhibition's title suggests, Philpot was a complex artist who wrestled with sometimes seemingly irreconcilable polarities. A high society portrait painter, he lived the high life. But he felt his creativity compromised in the execution of his flattering works. He had a deep-rooted respect for tradition but, ever curious, would always experiment and would go on to embrace artistic modernism. He oscillated between the aristocratic world and something rougher and tougher. Perhaps most difficult of all, he converted to Catholicism where his devout faith come up against his homosexual nature. It would seem these complexities could only be fully resolved through a negotiation of the mystery of the Incarnation, and through Philpot's fascination with, and honouring of, humanity in all its individual richness.

The First World War poet Siegfried Sassoon left a memorable and telling account of his sittings for Philpot which indicate the artist's compassionate humanism: 'The interior environment he had devised was a deliberately fastidious denial of wartime conditions, a delicate defence against the violence and ugly destruction which dominated the outside world.' Philpot was introduced to Sassoon by their mutual friend Robbie Ross, Oscar Wilde's most loyal supporter and literary executor. It was Ross, himself a convert, who had called for a priest to welcome Wilde into the Church on his deathbed. Sassoon, too, would convert to Catholicism in his later years.

Throughout his life Philpot had a profound religious faith. He won a scholarship to the Lambeth School of Art in 1900 where he created wood-engraved books and prints on religious themes informed by Arts and Crafts and Pre-Raphaelite book illustration. In an illustration to Chapter Four of the Song of Songs (1903-04), he depicts a lissom, high-cheek-boned youth with flowing locks, pining and recumbent. On the opposite page, the chapter begins: 'Behold, thou art fair my love … Thou hast dove's eyes within thy locks, thy hair is as a flock of goats that appear from mount Gilead.' His first painting to be accepted for exhibition by the Royal Academy of Arts was entitled The Elevation of the Host (1903), a work that sought to convey the drama and spectacle of Catholic liturgy.

Following a year studying at the Académie Julian in Paris, Philpot converted to Roman Catholicism in 1906. His parents were devout Baptists and his conversion caused a temporary rupture in his family. His Christmas card for that year, a wood engraving of the Nativity, has Mary bending over the sleeping Christchild in prayer. They are in a tiny hut. It is impossible for her to stand upright. There is a potent sense of confinement. Deep snow weighs down on the structure's roof. A tall, gaunt angel looks on, seeming to bear the Star of Bethlehem between his hands. A scroll unfurls the legend across the centre of the print: 'ET VERBUM CARO FACTUM EST.' As for so many, it appears Philpot was drawn to the central mystery of the Incarnation - the Enfleshment of the Word, and its manifold physical and emotional solaces - in his own journey of faith.

Philpot travelled widely through Europe and sought to emulate the techniques of the Old Masters, basing his paintings on exquisitely rendered draughtsmanship, and building up layers of rich glazes. He would regularly visit the National Gallery in London and would often make subtle quotations from art history. In The Sisters of the Artist, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1922, he depicted one of his sisters wearing a robe inspired by that worn in Veronese's Dream of Saint Helena. The Royal Academy curator Robin Gibson described the work as 'wilfully conservative … [with] a haunting, timeless quality and almost existentialist atmosphere'.

Philpot believed his 'subject' paintings - based, he said, on 'a theme drawn … from History, Myth or Allegory, or from literary or poetic invention' - provided opportunities for self-expression that were not necessarily possible in his commissioned portraiture. In A Street Accident (1925), he places a Pietà grouping within a modern street scene, in which a woman crouches over a supine and foreshortened figure of a man, which seems to reference Andrea Mantegna's celebrated Dead Christ in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. Philpot drew on his love of, and fascination with, theatre and performance in the framing of this scene of jostling humanity. The modern-dress transposition of a central religious icon (a compassionate woman cradling a man dead or in extremis in her lap) honours the popular religious tradition of the pageant plays from the medieval Mystery Cycles which adopted just such an approach of contemporary and topical re-enactments in the thronging thoroughfares of cities like Chester and York.

Philpot travelled to North Africa on numerous occasions. In the orientalist and homo-erotic L'Après-midi Tunisien, the odalisques of Delacroix are substituted by two men bearing carnations known to be the 'flower of love'. (Wilde's green carnation in Salome was a clear homosexual signifier and, significantly, Philpot had painted the transgressive, sexually unchained dancer of the Seven Veils back in 1907.) A red thread hanging from the wooden grill beside the younger man exemplifies the artist's mastery of visual illusion but there is surely a further symbolic meaning. It has been suggested that Philpot was evoking God's mercy and forgiveness of Rahab 'the harlot' which was denoted by a cord of red thread she tied to her window as a sign to keep her family safe during the storming of Jericho.

Philpot adopted a refreshingly unconventional approach to religious art, finding new perspectives and resonances. In The Angel of the Annunciation (1925), an auburn-haired Angel Gabriel has swooped down to a red-brick threshold of a modern house to inform the Virgin Mary that she is with child. This is a liminal moment par excellence and literally so thanks to Philpot's symbolic staging. There is a huge energy present: Gabriel's golden cloak billows behind him, full of a mighty celestial wind which has just deposited him on earth, from where he kneels in seeming supplication, his left hand stretched out towards Mary, his unseen interlocutor. In his right, he proffers not a lily but an anemone - linked both to the gored and desired body of Adonis and also symbolic of blood shed on the cross.

Philpot has parted ways with tradition by not depicting Mary and instead focusing on the Ariel-like Gabriel. However, in a reversal of the Renaissance technique of di sotto in sù (looking up from below) we the spectators are cast alongside her, looking down on the messenger-angel, witnessing this crucial moment in her presence and from her perspective. Mary's shadow looms in the foreground; her knitting needles and ball of wool placed to one side. Humble domesticity is interrupted. As he looks up at Mary, Gabriel, in dynamic close-up, reaches forward as if about to break through the picture plane, figuratively bringing the divine presence of the angel up close and personal, seemingly direct and unmediated, in a unique artistic perspective on the New Testament episode. This artistic inspiration does, in fact, recall once more the non-naturalistic forms of drama so long the mainstay of the popular tradition and certainly the lifeblood of early and religious theatres when characters would at times mingle with, and indeed challenge, the onlooking crowds.

Furthermore, as Simon Martin the curator makes clear: 'Philpot was an avid cinemagoer and his approach reflects an awareness of the cinematic close-up and shifting of frames in the telling of a story. The painting does not function as an object of devotion, like a Renaissance altarpiece might; it is an experiential rather than narrative image.' It can activate and energise devotion for all that, in the meditative and imaginative tradition of the Spiritual Exercises with their compositio loci which place the meditative subject right into the unfolding action.

In 1929, Philpot became the first president of the Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen, formed to celebrate the centenary of Catholic emancipation. Several of the works produced around this time - The Christmas Con-stellation, The Incredulity of St Thomas and St Michael - would have been destined for Guild exhibitions and churches. This appointment must have highlighted to Philpot the inherent conflicts between his Catholic faith and his homosexuality: his painting Resurgam (1929) (which translates from the Latin as "I shall rise again") encapsulates these tensions.

Ostensibly the painting quotes the format of Piero della Francesca's The Resurrection (Museo Civico di Sansepolcro, Tuscany). but it is undeniably a potent homoerotic presentation, with a sensuous depiction of a young, clean-shaven Christ emerging from the tomb while a soldier reclines alongside. The guard is shielding his eyes with his hand. This suggests he is dazzled by the risen Lord but also suggests he is a representative of blinkered and crushing authoritarianism. Philpot has followed the Gospel narrative: linen strips bind Christ's body, but these are flimsy. It is clear that Jesus is going to break these asunder, having conquered death. The symbolism is surely that the living death imposed by homophobia and its attendant strictures will also be conquered by Christ incarnate's Gospel of Love and Life. Bare branches before the tomb bear potent buds of new life. A rosy dawn rises over Christ, forming a potent arrowhead of resolve (a poignant and unwitting precursor of Nazism's pink triangle, today re-adopted as a symbol of liberation from hate). It is not enough to reduce the attractiveness of Catholicism to its aesthetic via pulchritudinis; there is clearly the strong pull of its radical, countercultural witnessing to an alternative way of being - a celebration of Otherness which rejects the constricting conformities of the Establishment. (The irony is of course that the institutional Church denounces what it identifies as the 'intrinsic moral disorder' of homosexual acts.)

After his death, a sensuous portrait of St Sebastian, tied to Philpot's studio's curtain rail, was found among his treasured possessions. Before the First World War, Philpot had created highly unusual figures of fragmented classical statues and androgynous figures at the bottom of the sea. One, posthumously named The Pearl (1914-18) evokes Christ's parable of the hidden Pearl of Great Price. It is hard not to detect in these works a sense of drowning and oblivion in the prevailing homophobic culture of intolerance, ignorance and bigotry in which the artist lived. Resurgam is a key work of resistance against this culture.

In the Transfiguration of Dionysos (1924), the beautiful bare-chested god of wine and the arts transforms his would-be enslavers and persecutors into dolphins which calls to mind WB Yeats's great poem 'Byzantium' (1930) with its evocation of the eternal struggles between the real and the ideal. The poem ends with the resonant line of a sea of creation that is 'dolphin-torn': life always impinges on art. Striking a different note, 'The Journey of the Spirit' (1921), likened by some critics to the monumental sculptural work of Michelangelo, was the most celebrated of Philpot's allegorical and Symbolist nude paintings. Its muscular classicism was hailed as 'thrilling and majestic', a timeless expression of heroic masculinity.

In 1930, Philpot travelled to New York with Henri Matisse to judge the Carnegie International Exhibition. Here he encountered, and was inspired by, the Harlem Renaissance. Having embraced the modernist and experimental zeitgeist, he moved to Paris where he dropped the society portraits and instead painted French Caribbean cabaret performers and nightclub doormen, friends, actors, ballet and circus performers with greater freedom than ever before.

He designed a costume for Satan in a theatrical adaptation of the infernal peers in Pandemonium in Milton's Paradise Lost. This costume design itself influenced his modernist painting of An Ascending Angel (1931) which had similar flame-like wings on wrists, ankles and shoulders. The critic at The Guardian declared it 'a striking and powerful design … [A] studio in Paris among the wild men of art is disturbing to an Old-masterish painter.'

In addition to providing one of the most substantial and sensitive artistic records of queer culture in Britain and Europe prior to the Second World War, Philpot's work is acclaimed for its sensitive portrayal of people of colour in a period when this was rare in Modern British art. The exhibition includes over thirty depictions of Black models. Unlike many earlier predecessors, Philpot did not depict his black sitters as servants or slaves or subordinates, nor as racist stereotypes. Rather than being pushed to the margins, they are the dignified focus of the work.

From 1929 onwards Philpot painted a series of portraits of a handsome Jamaican ship stoker called Henry Thomas, whom he also employed as a manservant. One of the most compelling of these is Balthazar (1929) in which the artist jettisoned the other Magi to focus entirely on the African king who brings myrrh to the baby Jesus. Almost all narrative elements are stripped away, except Balthazar's robe, the desert landscape, and the precious gift he conveys. His head held high, he is a figure of power and assurance.

One of the first depictions of Henry Thomas was again as Balthazar in The Threefold Epiphany which also refers to the Baptism in the Jordan and the Wedding Feast at Cana with each epiphany revealing something about Christ: his divine nature, as King and Messiah, and as miracle-worker. In the Baptism section, the figure removing his clothes in the background is an homage to Piero della Francesca's Baptism of Christ in the National Gallery. Poignantly, this painting was presented to the Newman Association in memory of the artist by his family.

Thomas became a Muse to Philpot. In Head of a Jamaican Man (Heroic Scale) (1937) the skin tones are sensitively realised with almost pointilliste dabs of colour. Thomas's eyes seem to brim with tears. He nevertheless holds us with his strong, upright gaze. After Philpot's death from a cerebral haemorrhage in 1937, there was a grand funeral in Westminster Cathedral. However, at his committal, only his family, his friend Lord Balniel, and Henry Thomas were present. In a poignant note left with a bouquet on the artist's grave, which was kept by the family, Thomas wrote: 'for memory to my dear master as well as my Father and brother to me. God blessed [sic] him and forgive him for his kind heart and human nature from his poor servant Henry.' These words are packed with so much. They trouble with a sense of possibly racialised and certainly class hierarchy but also evoke Catholic liturgy and a deep sense of humanity, compassion and love.

Such are the complexities of flesh and spirit Philpot's ever-evolving, beautiful and fascinating work negotiates in this superbly curated exhibition.

Catch it if you possibly can on its last day.

Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit

Pallant House Gallery,

Chichester

Sunday 23rd October 11am-5pm

www.pallant.org.uk

(01243) 774 557