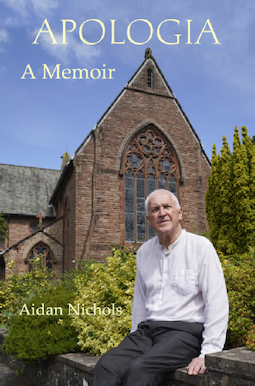

Aidan Nichols, Apologia: A Memoir

For 50 years Aidan Nichols has focussed his powerful mind on a wide variety of theological topics. Over the same period this English Dominican friar has acquired international renown as a conservative theologian, to the extent that he is now under a cloud in many Catholic quarters. He would reply that he has simply stayed in the mainstream of Catholic doctrine, which others have sought to divert.

One purpose of this memoir is to make clear his acceptance of Vatican II. He regards the texts of the Council as 'generally admirable' but blames deficiencies in the way in which they were read. Post-Vatican II leadership failed to integrate 'a fresh presentation of faith, worship, spirituality, the apostolate, and the priestly and Religious lives … with everything of value in the existing Church culture' (144). You don't need to be conservative to recognise the validity of this criticism.

So what would he desire to see change in today's rather etiolated Catholic culture? He seeks a 'hermeneutic of continuity' faithful to tradition but capable of speaking to the present age. Following his hero Balthasar he longs for a recovery of the converting power of beauty, conveyed through architecture, liturgy and sacred art. He wants an 'intelligent conservatism' in theology (79). A philosophically ordered teaching would use the concepts of being, cosmos, history, form and person to unfold the faith. Such a sacramentalised presentation would locate the heart of Christian revelation in 'the self-emptying of the Trinity in Jesus Christ by which reconciliation and deification are given to the redeemed' (98-99).

Nichols says that early in his life as a Dominican he realised that he would be called to oppose what he calls 'sociologically reductionist soteriologies' (58). I take this to mean accounts of salvation which give priority to how our faith answers this-wordly issues such as poverty, justice, peace, and sexuality. Following Benedict XVI he criticises the way in which the present culture operates a 'canonisation of subjectivity', which overrides objective moral teaching by reducing conscience to what each person feels is right (106).

Over the years, Aidan Nichols has offered astute criticism of the shallowness and self-centredness of contemporary Western culture. More controversially, he has attacked what he perceives as theological complicity with this culture. This led him to criticise some recent papal teaching. He publicly opposed Amoris Laetitia (2016) and the Abu Dhabi declaration on world religions (2019), both of which he sees as misleading. He co-signed open letters to the college of cardinals and college of bishops inviting them to issue corrections. I was startled to read that he even visited Moscow in hope of evoking a Russian Orthodox riposte, a candid admission that may rebound on him. He admits naively underestimating the impact of his actions (102-103). Its consequences for him have included alienation from his own Dominican province, where he is regarded as a polarizing presence.

Even an unsympathetic reader could admit the validity of some of his criticisms. The loss of definitive teaching reflected in poor catechesis is widely acknowledged among parish clergy. It is extraordinary that the traditional Latin Mass (in which I have no interest) has become a lightning rod for all sorts of tensions, its celebrants subject to censure. Secular culture with its weird obsessions does indeed have shaky foundations (we might cite the current 'trans' hysteria). There is also something disconcertingly prophetic in his assertion that there may be elements of papal teaching that come to be 'passed over' by bishops (cf 112). The book was concluded before Fiducia Supplicans, which several episcopal conferences have already announced will not be implemented in their territory.

The weakness of this book is its lack of engagement with the real world. Any parish priest who loves his people knows the struggles they go through, and the suffering they sometimes endure. The priest will know in himself the tension of wanting to be faithful to the teaching of the Church, and yet longing to meet people where they are. He may even understand that sometimes the Church can be brutal to its faithful. Ideal can collide with reality.

For example, I remember a woman whose application for an annulment had been granted, then denied on review, whereupon it was referred to the Roman Rota. She had heard nothing for five years and had no reply to correspondence. I wrote on her behalf and received no reply. At my request an auxiliary bishop then wrote inquiring about the case and he too received no reply. At least Amoris Laetitia should have ended such lofty indifference.

This is an important and challenging book, but it is let down by a pervasive stylistic quirk. Its author is addicted to breaking up sentences on with both parentheses AND dashes, which means that many sentences have to read two or three times to yield their meaning. Here is one of these hiccupping sentences: 'Still less was it the theological culture of the Ressourcement theologians to whom - more than (though by no means to the exclusion of) the Neo-Thomists - I was attached.' And that is one of the simpler examples.

The book ends with Nichols seeking admission to a Norbertine abbey of traditional observance in the United States, with the blessing of his Dominican confreres. Even if he succeeds in this desire it amounts to the marginalisation of a talented scholar. It would be a sad coda to a life of sustained theological reflection at the service of the Church. Speaking of which, his Stakhanovite work ethic has resulted in a prodigious outpouring of books and articles. What a pity this memoir does not end with a bibliography of his writings.

Aidan Nichols, Apologia: A Memoir is published by Gracewing, 2023 (£12.99).

See: www.gracewing.co.uk/page475.html