A Glorious Celebration of Churches

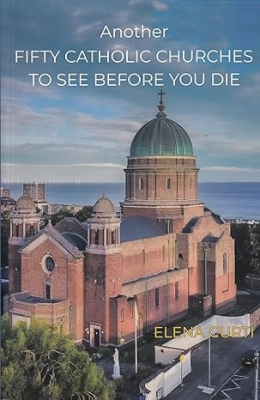

Following on from her superb Fifty Catholic Churches to See Before You Die, Elena Curti has provided a glorious sequel: Another Fifty Catholic Churches to See Before You Die.

These English and Welsh churches are arranged in alphabetical order from Arundel Cathedral to Worth Abbey. It is wonderful to behold Arundel's cathedral and castle high up on a ridge from on board a train across the water meadows. The circular part-subterranean church of Benedictine Worth Abbey resembles a flying saucer but communicates a powerful sense of the sacred.

Written in limpid prose, Curti's book grips with fascinating facts and an eye for arresting detail.

'There is a cheeriness about Clare Priory … the main house painted Suffolk Pink, the stick-man sculptures striding through the gardens.' Clare was the first house established by the Austin Friars in England, in 1248. More than 400 years after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, in 1953, the friars had the good fortune to return to this idyllic spot close to the ruins of Clare Castle, celebrating Mass in the billiard room for the first couple of years.

St Edward the Confessor in Clifford, West Yorkshire, and built of creamy Tadcaster limestone, could be in Tuscany or Normandy with its graceful Romanesque tower. J. A. Hansom's creation was based on a drawing of a fantasy church by a young Scot who was dying of consumption. The patrons included owners of a flax mill which gave work to poor Irish migrants and a recusant family with a castle. The church houses what has been described as 'the most beautiful statue of the Mother of God to be found in Christendom.' It was carved in Carrara marble in 1844 by the Jewish Karl Hoffmann (1816-77) who, it is said, converted to Catholicism after completing the work.

St Mary's Church, Harvington in Worcestershire, pre-dates Emancipation and is discreetly chapel-like. It houses the shrine of St John Wall OFM (1620-79), a Franciscan who ministered in the area and is thought to have lived in the adjoining Harvington Hall (where there are two fascinating recusant chapels). Caught up in the plot trumped up by Titus Oates, he was one of the last priests to be executed. The church also commemorates St Nicholas Owen (c. 1562-1606), a martyred Jesuit lay brother and a joiner renowned in the craft of constructing priest holes.

Down in Launceston, Cornwall, the hill Church of St Cuthbert Mayne (1911) is 'Byzantine with a Celtic twist.' Mayne himself was imprisoned in the castle across town prior to his execution. The church was designed by the antiquary brother of the Anglican convert who built the church and was its first priest.

The stunning St Francis of Assisi, Notting Hill, was built in one of London's most notorious slums, dominated by piggeries and potteries. 'Peep behind the tabernacle to see a dog with bared teeth supporting the monstrance throne - The Hound of Heaven.' (This reference made me return to the vagrant poet Francis Thompson's stirring contemporaneous poem of the same name which ends thus: 'Ah, fondest, blindest, weakest, I am He Whom thou seekest! Thou dravest love from thee, who dravest Me.')

Although the church is now in one of the most affluent parts of London there is social housing close by and in the courtyard is a memorial to parishioners who died in the Grenfell Tower fire in 2017.

Curti makes clear how many of her chosen churches were funded and indeed built by their poor communities, not least Irish migrants. They were 'gates of heaven' for the faithful and labours of love.

Westminster Cathedral boasts 129 kinds of marble, probably more than any other building in England, and including rare marbles used by ancient Greeks, Egyptians and Romans. The interior has been decorated by successive generations of artists. The site of the first London performance of Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius, the cathedral's acoustics are perfect for voice and organ.

Edith Arendrup (1846-1934) was an early settler in the hilly suburb of Wimbledon who bankrolled Sacred Heart. A scion of the Courtauld family, she converted to Catholicism in defiance of her family.

Another convert, Charles Scott-Murray, financed the building of St Peter, Marlow, Buckinghamshire: a tiny Gothic gem by A.W.N. Pugin 'with traditional furnishings including a piscina, sedilia and screens.' (Curti's cogent glossary explains all.)

Build a Baroque church on Merseyside in the middle of the Depression? An Irish priest who loved the ecclesiastical architecture of Portugal made it happen. He was Fr Thomas Mullins, nicknamed 'Pope Mullins;, such was his extraordinary confidence. Nor did he have any scruple in defying his bishop, who expressly told him not to build a dome. The Church of SS Peter, Paul and Philomena, also known as 'The Dome of Home', rises proudly from the highest point on the Wirral peninsula, visible from land and sea. It got its nickname during the Second World War from merchant seamen who knew they were safe when they spotted the familiar dome.'

Shrewsbury Cathedral rises above the town walls and River Severn with a steeply-pitched roof and graceful bellcote. It was integral to Newman's vision of a Catholic Second Spring. Inside, Margaret Rope's windows are distinctive for their deep, glowing colours and an abundance of detail: flowers, animals, symbols, people and places.

Clever detective work has identified that the subject of one particular window was the annual procession in honour of Catholic martyrs outside Tyburn Convent on 1 May, 1921 (103 years ago as I write). Worshippers kneel and a policeman stands in front of a London bus, arm aloft to stop the traffic. A mélange of martyrs and contemporary scenes in the window fuse past and present and are a reminder of the continuity of the faith and the Communion of Saints.

Curti's appendix on artists and architects relates how Rope, another convert, smoked cigars and drove motorcycles until she became a Carmelite nun in 1923. She is now recognised as one of the great stained-glass artists of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

The baptistery of Solihull's Our Lady of the Wayside 'stopped me in my tracks', writes Curti. Here, too, Elisabeth Frink's statue of the Risen Christ shows His resurrected body, different 'in some mysterious way'. Christ's two profiles alternately appear bearded-Jewish and Greek with a laurel crown.

Another 'glorious baptistery' is to be found in English Martyrs, Wallasey, a 'wonder on the Wirral'. 'Angels play chase with demons around the square font - by Herbert Tyson Smith - with its pyramid fish-scale cover topped by a cross.' The church is designed in Velarde's version of Romanesque, 'an endearing blend of playfulness and sophistication.' Influenced (like Hitchcock, another Catholic) by German expressionism, Velarde opposed the Modern Movement, and once wrote that the function of the true artist is 'to combine tradition and creativeness.'

At the end of each chapter, which homes in on a particular church, Curti provides further enticing suggestions for further visits. On the main road beneath Woodchester Priory, Stroud, is an early memorial to soldiers who died in the Great War. Families of all denominations were invited to add their loved ones' names. 'The list includes George Archer-Shee, killed at the age of 19 in 1914, and the subject of Terence Rattigan's play, The Winslow Boy.' G. K. Chesterton's parish church of St Teresa, St John Fisher and St Thomas More in Beaconsfield 'opened five years after Chesterton was received into the Church at a local hotel.'

Beautifully illustrated throughout, this book is an absolute joy to read, and to savour as a field guide on church sorties. With its excellent contextualising, and taken for all in all, it amounts to considerably more than the sum of its parts, transcending architectural history to offer a romantic, sensitive, cultural history of Catholicism across England and Wales.

Another Fifty Catholic Churches To See Before You Die: And Many More Worth A Detour

by Elena Curti

Gracewing www.gracewing.co.uk

Book: Fifty Catholic Churches to See Before You Die by Elena Curti: www.indcatholicnews.com/news/41071