Thomas Gumbleton - A True 'Doer Of The Word'

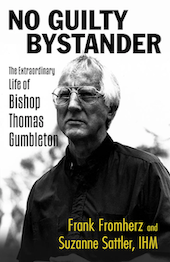

No Guilty Bystander. The Extraordinary Life of Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, by Frank Fromherz and Suzanne Sattler IHM. Orbis, Maryknoll (NY), 2023 270 pages plus notes.

On April 4, 2024 Bishop Thomas Gumbleton died in Detroit, the city where he had served as an auxiliary bishop from 1968 until his rather brutal forced resignation in 2006. Throughout that time and right down to his death, his motto was: "Be doers of the Word." As the title of this excellent biography by Frank Fromherz and Suzanne Sattler amply testifies, he lived out his motto to the full. The book's main title derives from 'Conjectures Of A Guilty Bystander', one of Thomas Merton's last books, a work in which he chronicled his realisation of the call to universal love. And Gumbleton's life was indeed 'extraordinary'.

It just so happens that his nickname on the sports field during his seminary years was 'Gump'. Any similarity to the figure played by Tom Hanks in the 1994 movie 'Forrest Gump' ends with that abbreviation of his name. Yet I thought of that film repeatedly while reading the Bishop's biography. By clever use of CGI and splicing of archive footage, Forrest Gump taught Elvis Presley his dance moves, met successive presidents, fought in Vietnam, became a sporting hero, unwittingly uncovered the Watergate scandal and shared in the early success of AppleCorp, before losing his childhood sweetheart to HIV.

Without any recourse to the conceits of novelists or the sleight of hand of filmmakers, Tom Gumbleton turns up in the struggle against the Vietnam War, confronting racism in the Catholic school system, visiting the US hostages held in Iran in December 1979, getting arrested at the US nuclear test-site in Nevada, opposing the US support of the government repression in El Salvador and Nicaragua in the 1980s, visiting hostages in Baghdad during the stand-off following Sadaam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait in 1990, supporting President Aristide against the US-backed coup in Haiti, speaking out against the US military response to 9/11, and visiting Afghanistan in June 2002 and Iraq in January 2003 (one of 8 trips to that country).

As first president of Pax Christi USA, Gumbleton was instrumental in the production of the US Bishops' pastoral letter, The Challenge of Peace (1983), rejected US nuclear weapons policy (describing the bombing of Hiroshima as America's "original sin"), advocated for conscientious objection for those in the armed forces and for the methods of non-violence beyond them, and critiqued 'Just War Theory'. After 9/11 he asked his brother bishops: "What kind of wisdom is it to carry out a war when we know the only outcome is going to be further war?" 21 years later the answer seems clear.

As well as his increasing prominence in speaking on matters of war and peace, he got caught up in some of the psychodramas which have beset the US Church through the last six decades. When his brother came out as gay this forced him to face up to his own previous attitudes towards homosexuality and rethink the Church's response. The upshot was that he ended up speaking at a New Ways Ministry symposium in Chicago in March, 1982: "The seminary formation I received was reinforced by the culture in which I grew up. It did not prepare me in any way to minister effectively to gay and lesbian people." Yet he was able to tell the delegates, "I am a bishop and I have a gay brother and it's okay and he's part of our family [and] his partner is accepted as part of our family."

Having spoken out on the issue of the ordination of women early on in that debate his chances of 'preferment' (to use that dreadful term) were shot, certainly once Pope John Paul II became Pope. As he ruefully admitted after his sacking as Bishop, "We have reverted to a church where bishops consider themselves as delegates of the pope." After the highwater mark of his piloting of the pastoral letter on peace, his place on the Bishops' Conference gradually became more and more marginal until he eventually stopped attending. Yet he was tolerated for a long time, despite crossing swords with various senior prelates. He was only defenestrated when he undertook advocacy on behalf of the victims of child abuse. Without flagging up his intention beforehand, he testified before the Ohio legislature in favour of lifting the statute of limitations to allow victims to hold the Church accountable - a move opposed by the state's bishops because of the potential financial implications. He argued: "Full disclosure of the abuse is essential to hold perpetrators and the church accountable, heal victims and restore the church's moral credibility." He was fired immediately, because he "broke communio with his brother bishops." The Ohio bishops' irritation is understandable. But to outside observers it just looked like business as usual, the curia putting the institution before the victims.

Why did he testify? Because he was asked by a victim he knew. Why did he undertake any of these controversial actions which peppered his ministry? For the same reason, not impulsively but because, after prayer, it seemed the right thing to do. "I got involved in so many issues of social justice by accepting the invitations. I never regretted it." What motivated him fundamentally was his understanding of Vatican II: "The church is here not to convert every individual person but … to bring about a transformation of the world so that it begins to look like the reign of God."

There is a paradox in the fact that this intensely private, introverted man ("at my happiest when I am sitting in a comfortable chair and reading a good book") should have become such a high profile public figure. Sent to Rome to learn canon law, he was an auxiliary bishop at the age of 38. Yet auxiliary he remained for nearly 40 years - a constant irritant to some and a sign of hope for many others. There's no need to canonise him just yet. But, like his contemporary, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, he represents a very different face of the Church and its hierarchy from the one presented by the likes of Cardinals Law and McCarrick, who found favour in the Vatican for so long. And while travelling the globe on various missions he remained always the humble pastor of a poor African-American parish in Detroit. Throughout it all, he followed the reassurance of Cardinal Dearden at his appointment "You don't have to change, just be yourself." We should be grateful that Tom Gumbleton followed his boss's advice.

For more information click here.