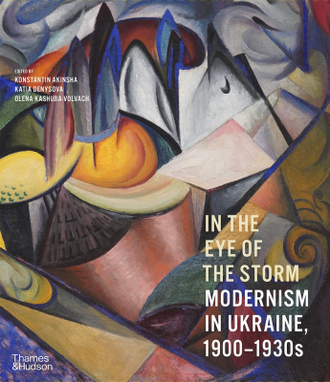

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900 - 1930

'The Eye of the Storm' at the Royal Academy explores dynamic Ukrainian art in the early twentieth century showing how Modernist artists established their cultural identity at a time of great national and international turbulence. Inspired by folk art and the Byzantine tradition, they created a definitive style independent from Russian and Soviet diktats.

Sixty five works are exhibited in three galleries. This joyous collection, an explosion of movement and colour has toured European capitals, although some countries have shown more works.

It is a pity that Oleksandr Murashako's stunning 'Annunciation' from the National Art Museum of Ukraine and other more explicitly religious works shown in Vienna's larger selection didn't make it to London. However, it is a remarkable achievement that the paintings safely crossed borders soon after Russia attacked Ukraine in 2022.

The Ukraine was divided up between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires at the turn of the twentieth century. No Ukrainian art academy existed, so many artists travelled, discovering developments such as Cubism and Futurism in Europe.

Inspired by European experimental creativity, those who returned to Ukraine shared these new ideas.

Davyd Burluick's colourful Carousel,1921, reinterprets a traditional Ukrainian subject with Cubist and Futurist influences, alongside Alexsandra Exter's Cubist masterpiece, 'Composition, Genoa,1912'and stylish 'Three Female Figures'1909-10.

In 1918 during the brief period of the Ukrainian People's Republic the development of modern Jewish Yiddish culture was expressed through the Art Section of the Kultur Lige. Artists like Issakhar Ber Ryback depicted Jewish daily life in works such as City (Shtetl), and El Lissitzky incorporated Yiddish text into his semi-abstract compositions. Sarah Shor's Sunrise places a praying figure amongst a geometric landscape.

The art movement sought to protect the rights of national minorities, including Jewish people. However, during the Ukrainian War of Independence, many Jewish people were subject to violent pogroms.

In 1921, after nearly five years of struggle in the Ukrainian War of Independence, the Red Army defeated the national Ukrainian forces. The new Soviet authorities at first allowed Ukraine to have some cultural autonomy, to appease local nationalism.

During this early Soviet period, a group of artists led by Mykhailo Boichuk, known as the Boichukists, reached out to ordinary Ukrainians. Drawing on Byzantine iconography, pre-Renaissance art and Ukrainian folk traditions they undertook state commissions to create murals for public spaces and buildings. Tymofii Boichuk, Mykhailo's brother, painted 'Women under the Apple Tree,' 1920, depicting iconically rosy cheeked peasants picking apples.

Volodyrmyr Burliuk's poignant portrait of a young 'Ukrainian Peasant Woman' 1910-11 is striking. She wears traditional costume with assorted bead necklaces and an Orthodox cross about her neck. She gazes piercingly defiant.

Kyrlo Hvozdyk was another member of the group and known as Ukraine's Gauguin. He painted rural scenes in egg tempera frescoes, later defaced. His striking Shepherds,1927, depicts shepherds looking at their sheep sheltering in a cave. He spent many years in internal exile and prison, managing to survive until 1981 but gave up painting.

Following Stalin's consolidation of power in 1930 his followers were accused of being 'Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists'. They were executed, their murals painted over or scraped off the walls, and their canvases were either hidden away or destroyed. Only smaller works survived.

Under the Russian Tsarist Empire, theatre in the Ukrainian language was banned, but the revolutions of 1917, the collapse of the Russian Empire and the foundation of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic led to a liberation of theatre in Ukraine.

Writers, directors, choreographers and artists explored what was possible on stage. Alexsandra Exter applied Cubist and Futurist principles to the scenography she designed. In 1918 she opened a private studio in Kyiv with a separate course on stage design. Acclaimed theatre designers, including Anatol Petrytskyi and Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov, were amongst her students.

A wonderful collection of posters from the Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine in Kyiv highlights impressive Expressionist theatre and costume design.

Vadym Meller's costume design in gouache on paper for the Friar in the play 'Mazepa' at the First Taras Shevchenko State Theatre, 1920 and his sketch of the 'Masks' for the Nijinska School of Movement are particularly captivating.

Hailed as the unknown genius of the Ukrainian avant-garde, Oleksandr Bohomazov was a prolific painter and theorist. He wrote numerous essays on colour theory and painting. 'Sharpening the Saws' ,1927, is a striking depiction of tall labourers using bold colours. Despite never leaving Ukraine, his close friendship with Exter allied him to Western art trends and he adapted Cubism and Futurism styles. He died from tuberculosis in 1930, aged 50.

Alexander Archipenko was one of the first artists to incorporate cubism in sculpture as seen in his marble and bronze ' Flat Torso',1914.

Ukrainian art has previously been seen part of 'Russian avant-garde.' 'The Eye of the Storm' corrects this, highlighting the story of Ukrainian modernism and the independent spirt of its people, when once again, the country is fighting for political independence and cultural autonomy

'Slava Ukraini'!

Until 13 October - Admission £17. Concessions available.

LINK

Royal Academy: www.royalacademy.org.uk/