50th anniversary of the fall of Cambodia

While Cambodia is now best-known for Angkor Wat and tourism, its enchantment hides a recent history and a poignancy beyond imagining.

Next week sees the 50th anniversary of the fall of its capital Phnom Penh on 17th April 1975, setting the stage for one of the most barbaric regimes in modern history. By mid-afternoon on that fateful day the whole population of this elegant city was being forced into the countryside by Cambodian rebel leader Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge army. Sidney Schanberg of the New York Times captured the brutality of those hours as patients in hospital, some still with saline drips attached to their arms, were pulled from their beds and thrust into the melée. There was no mercy.

It is a sombre anniversary, calling for reflection on the human condition, for Cambodia is by no means the only country which has seen unspeakable brutality. Our minds go to another auto-genocide with an April anniversary, to Rwanda where, in 1994, 800,000 people died in arm-to-arm conflict in a hundred days. And as the 80th anniversary of VE Day draws near, we dare not forget Hitler, or the cost of Western freedom.

Paris-educated Pol Pot and his university-educated colleagues, influenced by French philosopher Sartre, and by the models of Marx and Mao, would turn the nation into a death camp, a charnel house - from its ashes to arise an instant agrarian utopia. A new age would begin. It was now 'Year Zero'. Up to two million would die over the following three-and-a-half years, by being shot or struck with a hoe in the 'killing fields' or tortured to death in one of the 'liquidation' centres. First on the list were the military, the civic leaders, the intellectuals. Some of the country's most able young people were studying in the West. They received messages recalling them, offering plausible roles with the new government. They were met at the airport as their flights touched down, and driven straight to the nearby extermination centre.

Don Cormack, from the UK, was studying Chinese in Taiwan in 1974, when he received a message from OMF International, the mission agency he had joined, calling for unmarried volunteers to enter Cambodia. As the country could fall at any time, no families would be considered. The Church had grown fast, and more leaders were needed to teach hundreds of new believers. Cormack writes of how he 'went without a moment's hesitation', and began language study as soon as he arrived. After the country fell, Cormack would spend five years in the refugee camps which sprang up along the border with Thailand, where deeply-traumatised people told him their extraordinary escape stories. Only with Cormack's fluent Khmer could the West have received these first-hand accounts of Cambodia's plight.

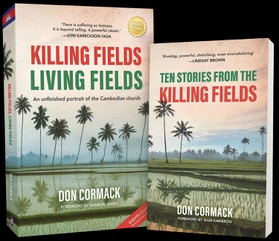

His award-winning classic Killing Fields, Living Fields first appeared in 1997. Its final edition is published on 15 April. Cormack shows a clear grasp of the wider historical and political contexts as he sets compelling stories of faith and courage against the backdrop of royal succession and the tyranny of Angka Loeu, the 'Organization on high'. There will always be evil dictators. Think Putin, Kim Jong-un, Assad, the Ayatollahs…. This is a book for our times.

In a refugee camp, after the Khmer Rouge had been overthrown in January 1979 by a Vietnamese invasion, Cormack was to meet, unawares, Comrade Duch, Pol Pot's chief executioner and 'Grand Inquisitor'. Duch had overseen the torture and death of tens of thousands, and personally signed the death warrants of some 1500 prisoners, who were first interrogated, then tortured to death. As his mother, a Christian, was close to death, Duch - knowing of a church in the refugee camp -sent a boy to find Cormack. His brief was clear for the few minutes he was granted: 'My mother is dying. She believes what you believe. Talk with her'.

Twenty years later, in 1999, news broke which took the world by storm. Nic Dunlop, a journalist from The Far East Economic Review had tracked Duch down in northwestern Cambodia, where he was living quietly as a humanitarian worker. Dunlop gained the scoop that Duch had become a Christian and been baptised three years earlier. In his eventual trial, Duch was the only Khmer Rouge leader to confess his crimes and ask the Cambodian people for forgiveness. 'My story is like that of the Apostle Paul', he said. Duch would die in prison in 2020 with a Bible and hymnbook beside his bed. By contrast, the last living founder of the Khmer Rouge, Khieu Samphan, remains unrepentant as he continues to serve out his life sentence, now aged 93.

Cormack's book opens with the beginnings of the Cambodian Protestant Church, some fifty years before the Khmer Rouge took control. While the Khmer Rouge have passed into the pages of history and infamy, the Church they sought so diligently to destroy is now well over 300,000-strong across the length and breadth of Cambodia, among the Khmer and the ethnic minorities.

Killing Fields, Living Fields (eighth and final edition) by Don Cormack is published by Dictum Press on 15 April, with a shorter edition Ten Stories from the Killing Fields.

Sidney Schanberg is remembered for his role in Roland Joffe's 1984 powerful Oscar-winning film 'The Killing Fields', which focused on the survival of Schanberg's Cambodian colleague Dith Pran after Western journalists such as Schanberg and Jon Swain had escaped to safety. Schanberg was played by Sam Waterston.